More homes should be the solution to Canada's housing shortage, but some argue opposite

A brief report by the Bank of Nova Scotia is the most cited reference when talking about Canada (with an average of 424 dwellings per 1,000 population ) lagging other G7 countries. A breakdown of population-adjusted housing stock for census metropolitan areas (CMAs) showed that at 360 dwellings per 1,000 population, the Toronto CMA had the lowest population-adjusted housing stock, which means inadequate housing supply is the issue there.

But not everyone agrees. For example, Steve Pomeroy of Focus Consulting Inc. argues that larger household sizes imply that Canada needs fewer homes than in other G7 European countries.

Because of larger family sizes (2.47 persons per household, compared to the G7 average of 2.31), “Canada needs to produce 405 homes for every 1,000 in new population, fewer than the G7 average of 431.” He said Canada has exceeded the number of dwellings needed to house its population since 2001, except for a few years.

Pomeroy is not alone in expressing skepticism about supply being the solution to the housing shortage and suggesting that Canada may not have a housing deficit, or one as large as Canada Mortgage and Housing Corp.’s estimate of needing to build 5.8 million new homes by 2030 to restore affordability.

Paul Kershaw, a professor at the University of British Columbia and founder of advocacy group Generation Squeeze, recently said in an op-ed that “the focus on ‘Build! Build! Build’ ignores that lack of supply isn’t the only, or even primary, factor influencing the price of rent and ownership.”

He pointed out that Scotiabank’s “data also shows that Alberta has lower levels of housing stock per capita than most other provinces, yet home prices in Alberta are about half as expensive as those in Ontario and B.C.”

Housing affordability is a complex problem and has no simple answers. But those who believe housing prices will not be impacted by more supply simultaneously argue for ramping up the supply of purpose-built rental (PBR) housing. If supply can’t impact prices, why will it impact rents?

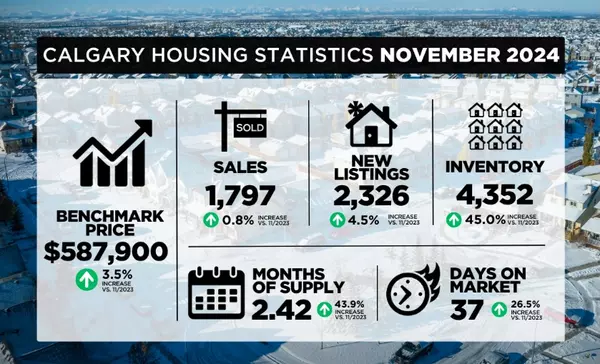

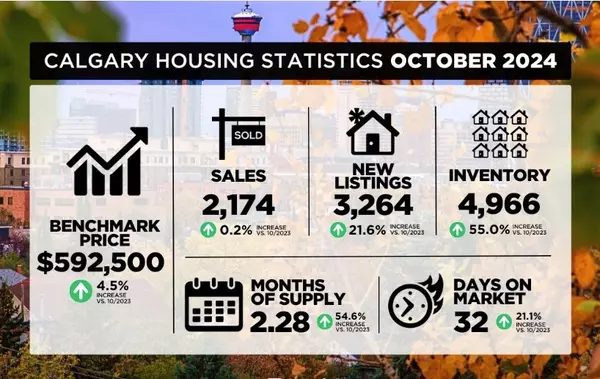

Housing affordability manifests itself at the local or city level. Alberta may not have a housing affordability problem overall, but Calgary and Edmonton do. The population-adjusted housing stock in that province’s two most populous cities is lower than in Montreal, Ottawa-Gatineau, Vancouver and Winnipeg.

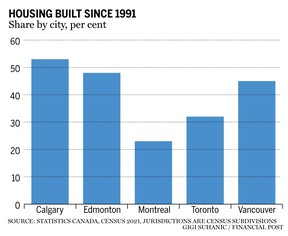

However, relatively lower housing prices in Calgary and Edmonton are a direct result of aggressive building of housing supply. These cities have been building housing at a much faster rate than other large cities in the past 35 years. Most homes today in Calgary did not exist in 1990. Almost half the homes in Edmonton have been built since 1991 compared to less than one in four homes in Montreal.

Although much less populous, Calgary and Edmonton have built far more homes since 1991 than Montreal. Furthermore, a dwelling in Calgary, on average, has 35 per cent more space than in Vancouver.

Conflating household size with affordability spells nothing but trouble unless you recognize that large household sizes can also be an outcome of worsening housing affordability. You must review housing conditions in developing countries where acute housing affordability challenges result in larger household sizes and overcrowding to understand the fallacy of using larger household sizes to undermine the push for more supply.

Keir Matthews-Hunter, a housing planner for the City of Toronto, has studied the link between the rate of household formation and rental housing supply in Canada and said rising housing costs have undermined the aspirations of young adults to maintain independent households.

In a paper published in Housing Studies, he said there’s a causal link between household formation (also known as the headship rate) and the supply of PBR housing. A “one per cent increase in the relative supply of purpose-built rental housing leads to 0.24 per cent and 0.14 per cent increases in the rates of family and non-family household formation of young adults.”

Put simply, without a sufficient supply of rental housing, young adults will delay forming their own households, so adult children will continue to lodge in their parents’ basements, resulting in larger household sizes, which is evidence of a lack of housing supply and not otherwise.

Housing Minister Sean Fraser recently acknowledged that despite the federal government’s renewed interest in housing, there were no silver bullets. The short-term solutions for improving housing affordability might be elusive, but what is critical is that public-sector policymakers cannot be swayed by supply skeptics who fail to appreciate the urgency to build more homes.

Building homes is more challenging at high interest rates than when interest rates were at record lows. A “wartime effort” is needed to build more homes. Tinkering at the margins will only worsen housing affordability.

Categories

Recent Posts